One thing is clear about the future: it’s murky.

Technology will bring a new age of prosperity and wonder! Technology will destroy our livelihoods and leave us slaves to robots! Something earthshaking is coming!

Or maybe this is a “tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.”

Let’s take a look.

The current fear–our jobs

The greatest fear we have, right now, is that we are being made obsolete by our own machine creations. That our work will be automated right out from under us.

But if we can automate most work, how quickly will we do it?

Seems like a simple question. But it’s not.

There is agreement that a great many work activities can be automated now. Note that’s not jobs automated—it’s the work activities within all the jobs. automation may break our jobs into machine digestible pieces, which is just a continuation of the chopping up of jobs that began in the 18th century with the introduction of water powered looms and culminated with the assembly line. We will delve more into the historical perspective a bit later.

In 2015, McKinsey “showed that currently demonstrated technologies could automate 45 percent of the activities people are paid to perform and that about 60 percent of all occupations could see 30 percent or more of their constituent activities automated, again with technologies available today.” (1) Globally, those work activities represent the equivalent of 1.1 billion workers and $15.8 trillion in wages. (2) Or, as the World Bank reported in 2016, “two-thirds of all jobs are susceptible to automation in the developing world, but the effects are moderated by lower wages and slower technology adoption.” (3)

But you cannot just eliminate tasks within jobs without endangering the number of jobs. While one potential future might have workers doing half as much for the same pay, most don’t. A widely referenced study by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne in 2013 using 2010 data estimated that “47 percent of total US employment is in the high risk category, meaning that associated occupations are potentially automatable over some unspecified number of years, perhaps a decade or two.” (4) This study did look at whole jobs and assigned probabilities of computerization for each of nine dimensions (such as negotiation, caring for others, manual dexterity), so each of 700 jobs has its own overall probability. High risk means that the job has a 70% or greater probability of automation within 10 years.

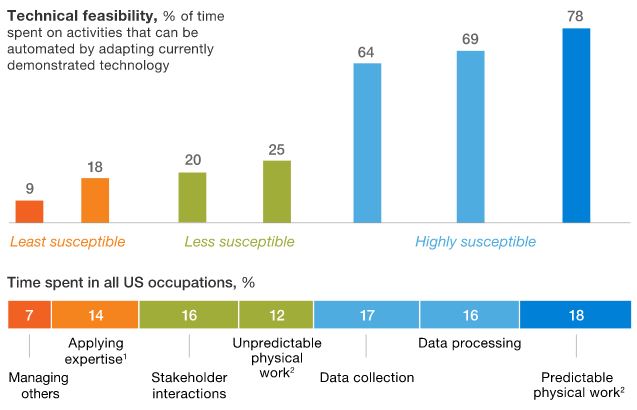

In 2016, McKinsey dug in again and produced this chart:

Tasks that occupy 51% of all work time in the U.S. today are highly susceptible to automation. Those are not all low-wage jobs either. Already machines using artificial intelligence are significantly better than experienced doctors at reading CT scans and X-rays. (5) Of course, some workers at risk are low-wage, like the fast food employees that the CEO of CKE Restaurants Andy Puzder would like to replace with robots because “they’re always polite, they always upsell, they never take a vacation, they never show up late, there’s never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex or race discrimination case.” (6)

Some economists argue that automation also creates new jobs as it destroys old ones. Blacksmiths and stable keepers did not fare well as Fords began to roam the world, but auto mechanics, oil field workers and motel keepers did. However, automation now focuses as much or more on thinking tasks as on mechanical tasks. Jobs that Frey and Osborne rate as most likely to be automated (98 or 99% probability) include insurance underwriters, tax preparers, loan officers, insurance appraisers, credit analysts, claims adjusters, and bookkeepers. The range of things that humans can do better than machines may shrink faster than new human tasks are created .

Is it a slam dunk?

Of course, factors other than technical feasibility enter into any decision to replace a person with a machine: the cost of the machine, the cost of labor, even interest rates and CEO prejudices come into play. But one real catch to whether this change will occur quickly lies in the difficulty of successfully changing organizational processes—because that’s what it means to automate work activities and reorganize jobs. Although we’ve been trying to do this since the dawn of machines, we’ve been at it most seriously since computers became common in the 1970s and 1980s. Yet “most studies still show a 60-70% failure rate for organizational change projects–a statistic that has stayed constant from the 1970’s.” (7) According to Gartner Group, automation-driven changes, like private cloud implementations, can have even higher failure rates—as high as 95%. (8)

The biggest cause of all these failures? The most common problem by far is the interface between the people and the automation—that is, failing to change the work processes, failing to design automation to interact with people, and failing to sufficiently train the people who must use new processes and interact with new machines or software. A 2011 Swedish survey of managers found that “seventy-five percent of managers of all ages admitted to using an open-source tool or spreadsheet—or simply refusing to use the system—if the interface is hard to use.” If the managers won’t use it, will anyone else? (9)

Two of the biggest automation introduction disasters cost the U.K. National Health System £10 billion and the U.S. Air Force $1 billion, but it’s easy to find automation project failures in every industry, including computers: HP reportedly lost $160 million on one project. (10) Does this shed some light on why non-farm business labor productivity has increased an average of 1.9% per year since 1969, compared to 3.4% annual increases from 1948 through 1968, pre-computerization? (11) Or maybe why GDP grew only 2.6% per year after 1979, compared to 3.9% from 1948 to 1979? (12,13) Still, we keep trying, and we’re not likely to stop.

But we both digress and jump ahead of our story.

Revolutions: past and present

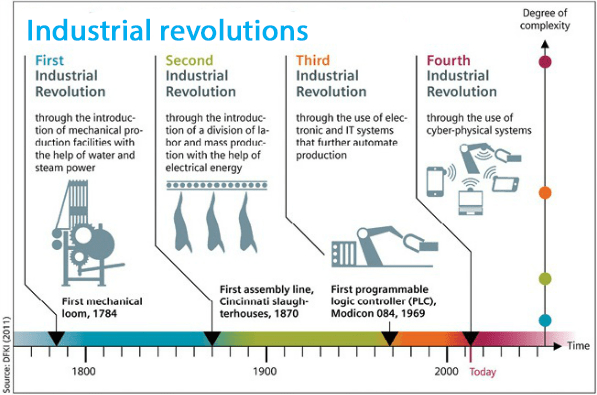

There is a broader perspective on job automation that we must examine and the clue to that perspective comes from the recent World Economic Forum at Davos. One of this year’s topics was a Fourth Industrial Revolution based on artificial intelligence and biotechnology, among other emerging technologies. (See list on page 9.) For completeness sake, the first industrial revolution encompassed coal, iron and steam, the second one electricity and steel, and third included the automobile and oil. All four revolutions brought colossal changes to the affected societies—remember the days before highways, suburbs and fast food?–but the fourth stands to be the most massive change yet: we may be able to transform the earth, make all people prosperous, and even create machines that are more intelligent than we are. Just as railroads and electricity brought huge changes in human society in the 19th and 20th centuries, collapsing distances and making possible a vast array of new devices and capabilities (light bulbs, radios, TVs). With nano-sensors, super thin materials and chemicals from renewable micro-organisms, combined with AI and biotechnology, we are poised for an even greater transformation in the 21st. For example, nano-sensors might allow us to avoid serious disease or deterioration and greatly extend our active lifespan. For example, could monitor plaque buildup in your arteries, or an engineered microbe might actually remove it.

In fact, a group of economists, sometimes known as evolutionary economists, have done broad research into how technology and innovation have driven economic growth and social change in the past. They include Chris Freeman in the U.K., Francisco Louçã in Portugal, Carlota Perez of Venezuela, and William R. Thompson of the U.S. They trace their roots to the early political economists, such as Adam Smith and Karl Marx, and later to Joseph Schumpeter. It was Schumpeter who coined the term “creative destruction,” that is in vogue among entrepreneurs, especially in Silicon Valley. Creative destruction is the capitalist “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” (14) This is the classic capitalist process that destroys old jobs and creates new ones: the rise of web-based music providers like iTunes and Spotify and the decline of the great vinyl and CD music publishers is a good example.

Schumpeter focused mainly on innovation as the driver of change, but his evolutionary economist successors go further to argue that “the evolution of the global economy depends on the interaction and co-evolution of several subsystems of society…certainly including technology and science, but also politics, economics, and culture.” (15) For example, mechanical looms replaced home-based weaving and eliminated a whole class of artisans by relying on unskilled labor. Railroads required precise timekeeping across broad territories and prompted growth of the first large, distributed organizations, managed via electric communications (the telegraph). Railroads and factories not only rigidified time by standardizing it across the whole planet, they also led to the previously unimagined concept that “time is money.” Faster transport meant more goods could be sold in a given timespan, and large investments in machines could be paid for more quickly if the machines ran longer each day.

Regular patterns in history?

What is especially noteworthy, and intriguing, about these evolutionary economists is that, although they have different points of emphasis, they all see a regular recurring pattern in socio-economic history. Specifically, they point to a common pattern in the periods of rapid economic growth since capitalism took off with the British Industrial Revolution. First, there is always a cluster of technologies that together enable a significant jump in productivity, first in one part of the economy—the leading sector–but then broadly across the whole economy. The first revolution, for example, started with textile factories powered by water and steam replacing skilled artisans working at home or in small shops. Steam-powered looms using stored energy (coal) and run by unskilled labor (often children) vastly increased cloth production. The example of this success sparked the use of steam power throughout the British economy, most notably in transport (railroads).

Then as the technologies are widely adopted, the type of work and the way the work is done undergoes significant changes. The second industrial revolution brought oil, steel, chemicals, electricity, and Ford-style mass production. In the heyday of manufacturing, one worker might specialize in assembling the casing of a motor, and a factory might specialize in producing starter motors for automobiles. Workers were by then several steps removed from a finished product: they no longer had the satisfaction of creating a complete product. Ford increased the pay of his workers not only so they afford a Model T but so they would keep working on the mind-numbing assembly line. This effect, which Marx called “alienation,” is echoed today in the further splitting up of meaningful jobs into atomistic tasks suitable for automation. The tasks remaining for humans can be as mind numbing as the those of the workers on Ford’s assembly line.

Finally, the scale of the change affects both institutions and politics, and the society undergoes considerable tumult as new industries seek to establish themselves alongside the old ones. In the third revolution, for example, when computer automation moved into factories and offices manufacturing’s share of total employment fell from about 25% to barely 8%, with total manufacturing jobs peaking at 19.4 million in 1979 before falling to 11.5 million in 2010. (16) . (This happened despite manufacturing remaining about constant at roughly 12% of GDP every year from 1960 to 2011.) Similarly, a host of clerical workers disappeared from insurance companies and banks as mainframes moved in during the 1970s and 80s. Typing pools and even secretaries vanished across all industries as PCs appeared on office desks. Whole cohorts of low-wage clerks were driven into health care or fast food emporiums. But consider the wider changes. PCs not only eliminated typists and stenographers, they also rearranged who did what and changes expectations for clerical and non-clerical workers. Managers kept their own schedules, wrote their own memos and worked longer hours; it no longer took several days to change and re-distribute a document; the art of dictation, spelling, and perhaps forethought declined, and vice-presidents felt compelled to “improve” everything that crossed their paths.

http://twoblokes.net/2017/07/25/objects-are-not-as-close-part-2