Really? Great surges?

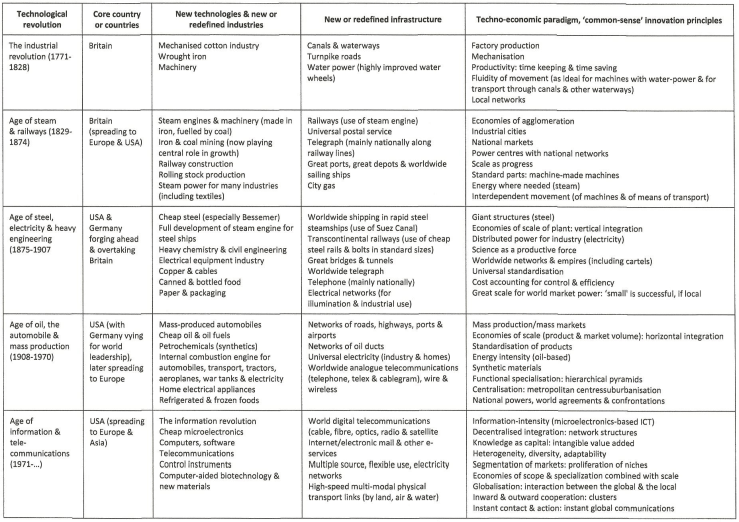

Evolutionary economists take a finer grained approach to describing change than the industrial revolutions identified by traditional economists. Instead they identify waves or surges of growth and change so that the First Industrial Revolution, for instance, encompasses two waves, one based on water power and one based on coal and steam. In this case, both waves started with the use of machines in textile production and then spread to transportation (canals first and then railroads) and both were in Britain, so they tended to be lumped together in traditional economic descriptions even though they were separated by several decades. The idea of economic waves was first proposed by Nikolai Kondratiev in 1922 and later picked up by Schumpeter, but their analyses were incomplete. Only in the last 20 years were these ideas fully enough developed to explain broad swaths of economic history.

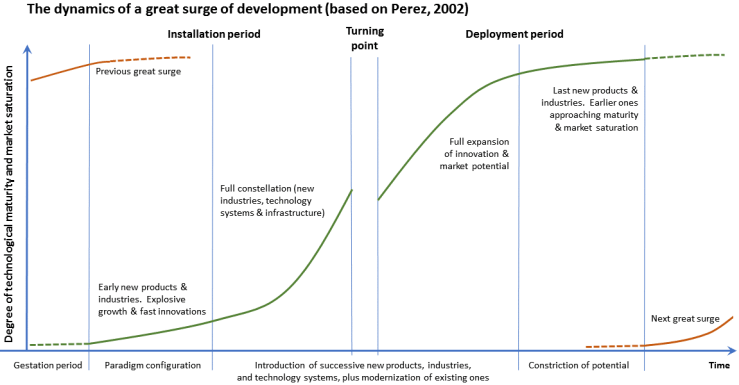

Economic surges, particularly those in the last 350 years, possess certain defining characteristics. First, each surge coincides with the appearance of a new and greater source of energy and a set of innovations which take particular advantage of the new power source (or just of the availability of more energy) to create much new wealth. The wave appears first in one leading economy, such as the U.K. or the U.S., and unfolds in stages. (See diagram below). The initial stage, called the installation period, begins during the previous surge as a new techno-economic paradigm forms.

Each surge is powered by speculative financial capital, and a few people and industries accumulate very great wealth during the installation period of a surge. As the change spreads, the labor force, and society as a whole, adapts–that is, they move into new jobs, though not docilely. In each surge, there is typically a speculative bubble and a collapse, as well as significant internal and international strife, strikes, trade wars, and real war. For example, in the third wave we saw the rise of the robber barons—Andrew Carnegie in steel, J.B. Duke in tobacco, Jay Gould in railroads, Andrew Mellon in aluminum, J.P. Morgan in mergers, John D. Rockefeller in oil—and then the big anti-trust laws in 1890 and 1914. The later part of this wave saw the formation of industrial unions and their final success after the 1920’s real estate bubble burst and the Great Depression set in. World War I and II both had roots in the third wave, and the second war, with its huge government sponsored industrial expansion, launched the great post-war boom of the fourth wave. But again, typically, as societal wealth grows more rapidly in the deployment phase, the political system negotiates a more equitable distribution of the economic gains, and tensions subside.

| Leading sector timing and indicators, 15th to 21st centuries | |||

| Lead economy | Leading sector | Start-up phase

(installation) |

High growth phase

(deployment) |

| Portugal | Guinea gold | 1430-460 | 1460-1494 |

| Indian pepper | 1494-1516 | 1516-1540 | |

| Netherlands | Baltic, Atlantic trade | 1540-1560 | 1560-1580 |

| Eastern trade | 1580-1609 | 1609-1640 | |

| Britain | Amerasian trade (sugar) | 1640-1660 | 1660-1688 |

| Amerasian trade | 1688-1713 | 1713-1740 | |

| Britain | Cotton, iron | 1740-1763 | 1763-1792 |

| Railroads, steam | 1792-1815 | 1815-1850 | |

| United States | Steel, chemicals, electronics | 1850-1873 | 1873-1914 |

| Motor vehicles, aviation, electronics | 1914-1945 | 1945-1973 | |

| United States | Information industries | 1973-2000 | 2000-20?? |

| ?? | Artificial intelligence, biotech | ?? | ?? |

Are we ready for another surge?

Although the waves have similarities, they are obviously not identical, and the outcome of each wave is not pre-determined. Nor is the leading economy guaranteed permanent success. Portugal and the Netherlands had a turn before the British, and the U.S. succeeded the U.K. Carlota Perez, one of the leading contemporary ‘wave’ theorists, argues that the next surge could be a “green” one, powered by renewable energy, closed loop resourcing, and the rise of several billion people into mass consumption lifestyles. If her vision comes to pass, it has the added promise of heading off the catastrophe posed by climate change—which would likely destroy any surge that doesn’t address it. For the sake of the current discussion, if not for our mental health, let’s assume that we will find a way to head off a climate catastrophe. How are we doing in setting the stage for another rapid economic surge that will generate a rapid automation of existing work?

Five Great Surges of Development (according to Perez)

Typically, according to Perez, each surge begins with a period driven by financial capital searching for new ways to make money when the technologies of the previous wave can no longer drive large profits. This search by unfettered finance drives a bubble prosperity that inevitably collapses into a recession or worse. This first phase, which Perez calls the “installation phase,” is characterized by growing income inequality. (Remember the robber barons? How about Larry Ellison, Bill Gates, Peter Thiel?) Dissatisfaction with the inequality and the collapse allow governments to chart a course for the next surge of growth, which Perez calls the “deployment phase.” (20)

Perez describes the last complete two-phase growth surge:

In 1908, Ford’s model-T inaugurated the Age of the Automobile and Mass Production in the United States. The great crash of 1929 ended the Roaring Twenties frenzy and led to the longest post-collapse recessive period to date: the 1930s. Resistance to the New Deal may be seen as one of the root causes of the prolonged stagnation. It took the experience of government-industry collaboration during World War II to enable acceptance of the full Welfare State and the Keynesian policies and institutions that facilitated the greatest economic boom in history. (19, p.213)

The post-war boom petered out in the 1970s and a new installation period based on information, computers, and telecommunications began. Bubbles based on the Internet and on complex, computerized financial instruments collapsed in 2001 and 2008. Thus, we should be primed for another economic surge. Are we?

What do we need, what do we have—what do we lack?

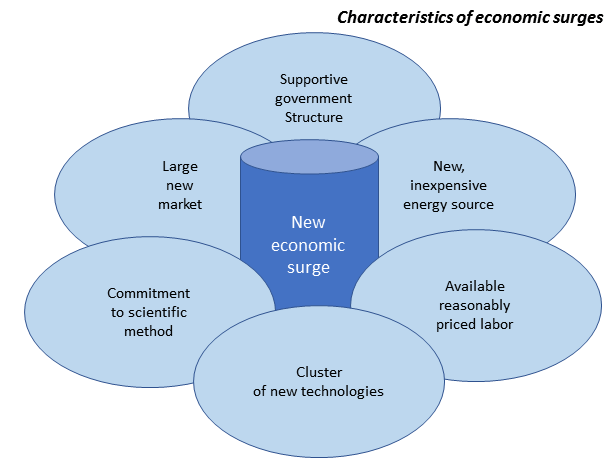

To answer this we can first note that previous economic surges shared several characteristics:

- A cluster of new technologies that amplified each other and ultimately affected large segments of the economy—like automobiles and suburban housing growth after World War II.

- A relatively inexpensive, new energy source—oil for the post-war boom.

- A commitment to a scientific approach of applying technology along with a belief that improvements are both possible and desirable.

- Available reasonably priced labor and a clear, large economic value—both resulting from the post-war baby boom.

- A supportive government structure, like the Bretton Woods post-war conference that established the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

- A large new market—like the auto-driven suburban build-out after World War II.

And we do have an unusually large and promising set of emerging technologies (as listed by the World Economic Forum) (21):

- Self-driving vehicles.

- Nano-sensors that can connect almost anything to anything else.

- Perovskite solar cells that are lighter and cheaper than conventional solar cells.

- New batteries that would make large-scale power storage possible.

- Open artificial intelligence ecosystem.

- Two-dimensional (super thin) materials.

- Systems metabolic engineering, which gets chemicals from renewable micro-organisms.

- Organs on a chip for medical testing.

- Optogenetics, which uses light to control modified neurons.

- The blockchain, which is a revolutionary decentralized trust system.

http://twoblokes.net/2017/07/25/objects-are-not-as-close-part-3